In Eyes Wide Shut, when Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) visits a jazz club in the wee hours of the night, approximately half past 12, he sees his old medical school classmate Nick Nightingale (Todd Field) on the piano finish up a jazz set. When Nick comes to Bill’s table, we see someone else – someone who looks eerily like filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, at the table across the aisle.

It is in this moment that the film reconfigures itself into something completely different than what it was initially. It’s also not surprising that this is the moment when Nick reveals to Bill that he plays blindfolded in an unknown location for which there is a password and which Bill should absolutely not go to.

It’s not surprising that in this scene in particular, Tom Cruise conjures up one of the most terrifying faces he has ever given in a movie – a face of bewilderment, mania, and above all, sadistic curiosity. But the figure at the other table is not Kubrick at all. It’s someone who looks like him. The false and ambiguous identity becomes a curiously central pillar of the film.

Eyes Wide Shut was released posthumously following Kubrick’s sudden death on March 7, 1999. It has been suggested that the movie is “incomplete,” with Kubrick having only screened a first cut for Warner Brothers a few days before his death. Being 70 at the time of his passing, Kubrick undoubtedly had his own mortality on his mind.

His cinema has been defined as an extension of himself, perhaps more than any other contemporary filmmaker, not only because of the obsessiveness with which he controlled his productions and aesthetics, but also in the way his films all felt eerily preordained. Spielberg noted quite famously while making A.I. Artificial Intelligence from Kubrick’s extensive notes and written drafts that he felt Kubrick’s ghost was directing the movie.

Likewise, as Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, feels like it’s haunted by him. Augmenting its feelings of dread and horror is the consistent level of distrust and paranoia that envelops Bill Harford as the film goes on.

Even before the jazz club scene, which is the sort of ‘through the looking glass’ moment, there is a conversation Bill has with Alice (an ironically named Nicole Kidman) where their relationship dynamic is near-permanently frayed by Alice revealing she was ready to throw her entire future with Bill away for a handsome naval officer. Bill is continuously haunted by his own imagination of a sexual encounter between Alice and the officer. As he traverses the city, these images keep coming back to him, and the movie’s imagery becomes more and more conscious of space within the frame.

Kubrick’s camera scans the streets and interior spaces of Bill’s apartment with ghostly diffused light emanating from Christmas trees, the street lamps, the moon, candles, and the neon signs that feel both warm and discomfiting that make each space feel like it exists in a parallel dimension askew to everything else.

The film was made in London mostly in sound studios which makes many of the New York scenes feel like they exist in a parallel dimension. The streets are a little too wide, a little too empty, the lights a little too luminous and void of any of that damp, steamy, claustrophobia you usually get from New York films actually shot on location.

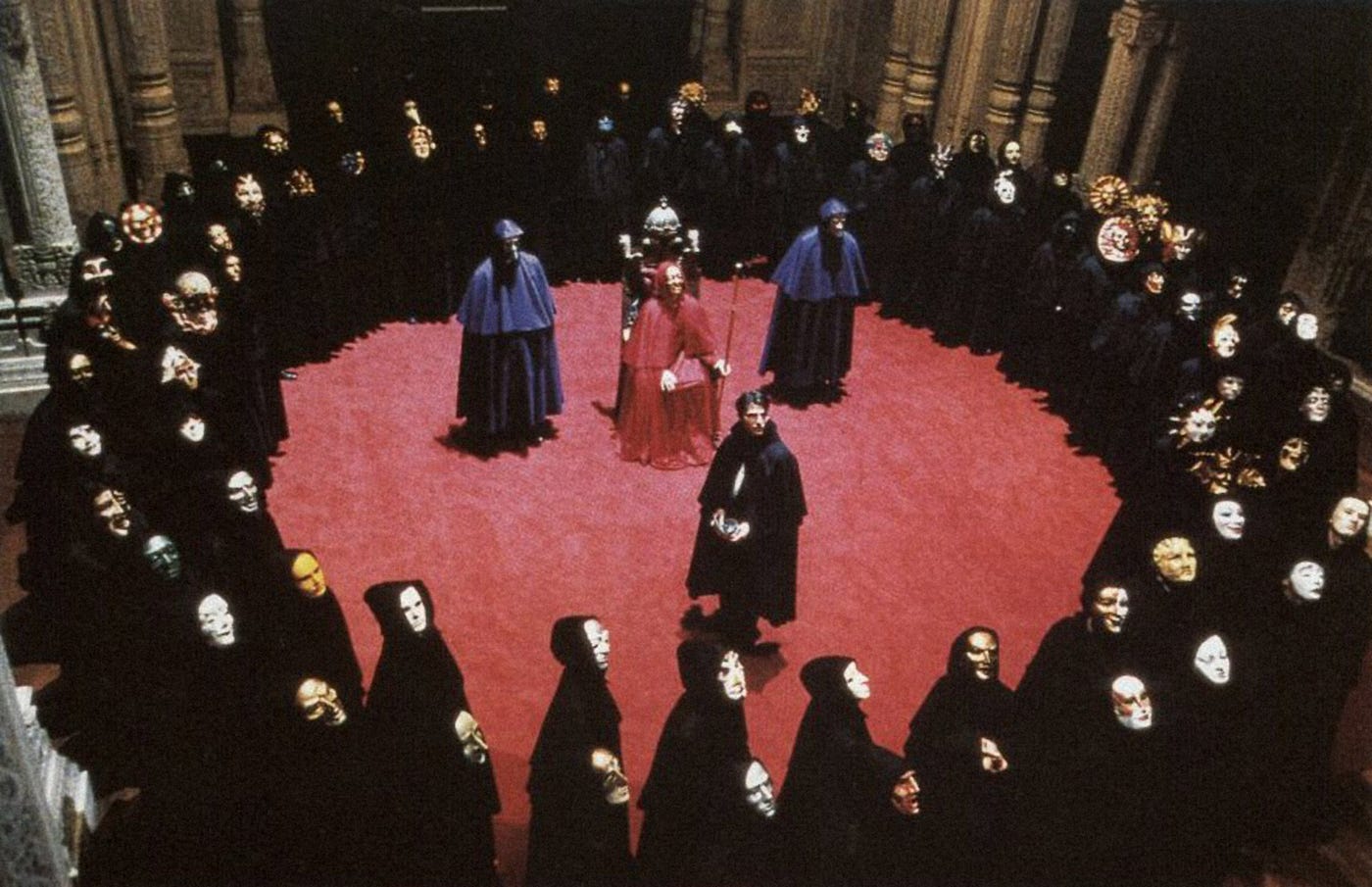

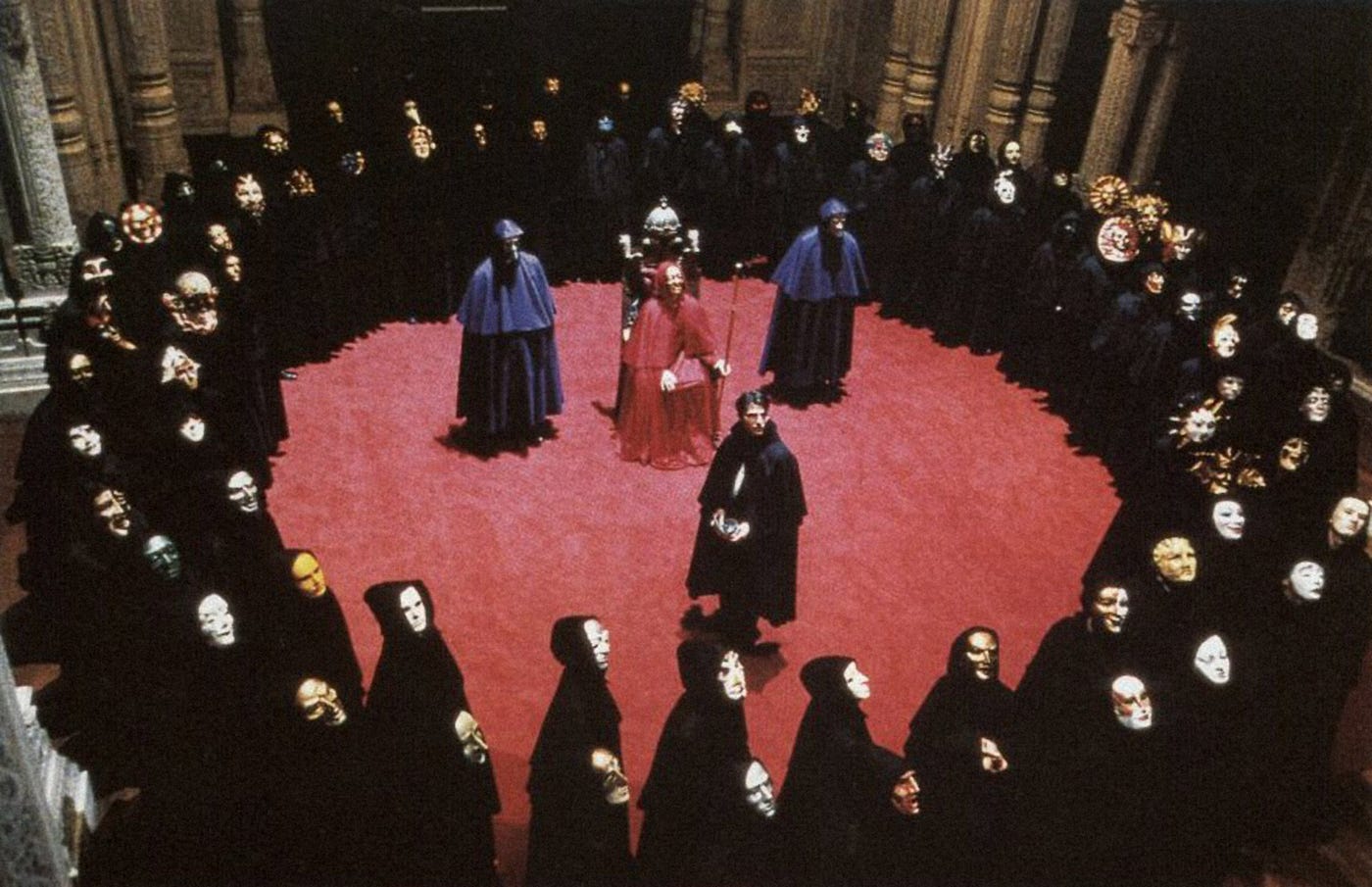

This spacing effect helps to make the corners of the streets, bars, costume shops, and houses seem to be hiding something. Kubrick utilizes the camera brilliantly in excavating space to tilt it off balance at every instance. In the sex cult orgy, the masks themselves, enveloping identity in ghostly apparition, become a source of paranoia for Bill and the audience. He, of course, is found out quite quickly, and immediately, we begin to notice the others give slight side glances towards him.

Every time a character approaches him, there is an anxiety that fills the space. Bill wanders aimlessly at night through the streets several times in the movie, but it’s after the party where it seems to become peppered with suspicious characters. Kubrick centers Cruise in the frame but the wide shot allows for the street corners to become alternate points of interest.

Because the streets of Kubrick’s New York are not crowded, the suspense is instead built the way horror films do in empty spaces: by creating multiple points of interest and using foreground and background, shot-reverse-shot to build anticipation between the two characters.

In the pool hall scene between Bill and Victor Zeigler (Sydney Pollack), the camera creates a resonant distance between the two as Victor reveals to Bill that he was at the party and complicit in having Bill followed. All of a sudden, it feels like Bill is in danger even in the presence of a friend. Even in this scene, the space feels like it exists apart from the rest of the film’s world, and that Bill is seemingly trapped there with Ziegler.

Cruise is once again positioned in the foreground with Zeigler in the back, like a phantom, and we come to the realization that earlier in the party, a couple had looked in Bill’s direction and nodded. Ghosts and ghouls are not explicit in Eyes Wide Shut but characters are treated with the same level of ambiguity in both identity and position.

In a microcosmic sense, all of the paranoia in the movie also emanates from that seed Alice places in Bill’s mind about the naval officer. That the permanent sense of distrust in their marriage is what rips open the void that Bill falls into at night.

Mirrors play a crucial role in how Bill and Alice’s dynamic is set up. The way they look at themselves as they caress each other in front of the mirror is, at surface, sensual but Kubrick makes sure things aren’t totally comfortable. Their stares point like a loaded gun, filled with longing, desire, contempt, and sadness all in one. Each of the domestic scenes in the movie feels off-kilter, and it wasn’t lost on Kubrick that Cruise and Kidman’s real-life marriage would play a pivotal role in the dynamics of the movie. Kubrick kept the two actors separate for most of the shoot, saying they could only interact during a scene.

Perhaps the most disturbing scene in the film comes during the daytime when Bill goes to return his costume to the proprietor Milich, who then coyly offers his underage daughter out to him for sexual favors. Bill realizes that she is being prostituted and the demons of sexual depravity from his fever dream through the cult seem to have ruptured and escaped into his normal life.

The sequence comes so nonchalantly, and it turns the secret and conspiracy of sex trafficking into an everyday ordeal. It warps reality and alters the mind to consider conspiracy to be all around rather than hidden in the shadows.

As much as the great auteurs of mid-century Hollywood and New Hollywood are now creating self-reflective films about their own careers and mortality, Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut stands as a movie that embodies his being.

He did not know he was going to die soon after he finished it, but like all of his movies, the meticulousness of its creation and staging turn it into a sort of host for his spirit. In Vincent LoBrutto’s Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, he mentions that sex and the evil nature of man were ingredients that appealed to Kubrick. He ends up turning his swansong into a film of unique power and terrifying observation, as haunted a film as there has ever been.