Cats have come a long way in horror over the years. Their primary presence used to be for cheap scares; if the killer or monster wasn’t around but it had been a while since the last jolt, an AD would toss a cat in front of the camera toward the lead actor, and they would jump, we would jump, the cat scurries off, and that’s that. “Where did that cat come from?” is a foolish question to ask seriously. They didn’t exist before their entrance and stopped existing after that.

Of course, this rather indifferent (if almost cruel) treatment of cats compared to dogs and other animals was born from a myth that cats could not be trained to “act” in the same way. It’s not easy, mind you, but the idea that it was “impossible” took hold, a stigma that’s been hard to shake.

Since a dog is easier to train, it naturally meant they got a better shot at Hollywood stardom, with cats being used quickly for non-specific actions more often than not. Even a trained cat can decide to just do its own thing if it feels like it—it’s part of the appeal! But that makes them something of a red flag for a movie set, where time is everything, and hitting your mark is crucial to a successful take.

But people also believe that cats (particularly black ones) are a sign of bad omens, friends to witches, and other silly superstitious stuff. So naturally, there’s always been a place for them in horror movies, going back to the Universal Monster days in the early 1930s.

These older appearances usually required very little trickery or training from the filmmakers; they could film the little fella running across the room or even sitting quietly and have Boris Karloff or whoever merely tell the other characters (read: us in the audience) that the cat was evil. Due to the aforementioned superstitions, that would be all the audience needed to be sold on the idea. The Tomb of Ligeia and countless adaptations of Poe’s The Black Cat all banked heavily on such preconceived notions.

Still, someone would occasionally try to get them to do a little more “acting.“ A prime example would be 1969’s obscure thriller Eye of the Cat, written by none other than Psycho scribe Joseph Stefano. The movie concerns a man who wants to scam his rich aunt out of her inheritance, but to do so, he needs to get past her army of loyal cats.

It’s a good movie, but there are countless shots of the villains pretending to be menaced by cats who are clearly not actually interested in anything. The editor tries his best to cut away before it’s obvious, but you don’t even have to look closely to see them often running past the person they’re supposedly chasing, or fighting each other when their target is the human next to them. It’s kind of cute, to be honest, but it obviously harms the impact of those scenes and presumably didn’t help boost feline opportunities in the horror genre.

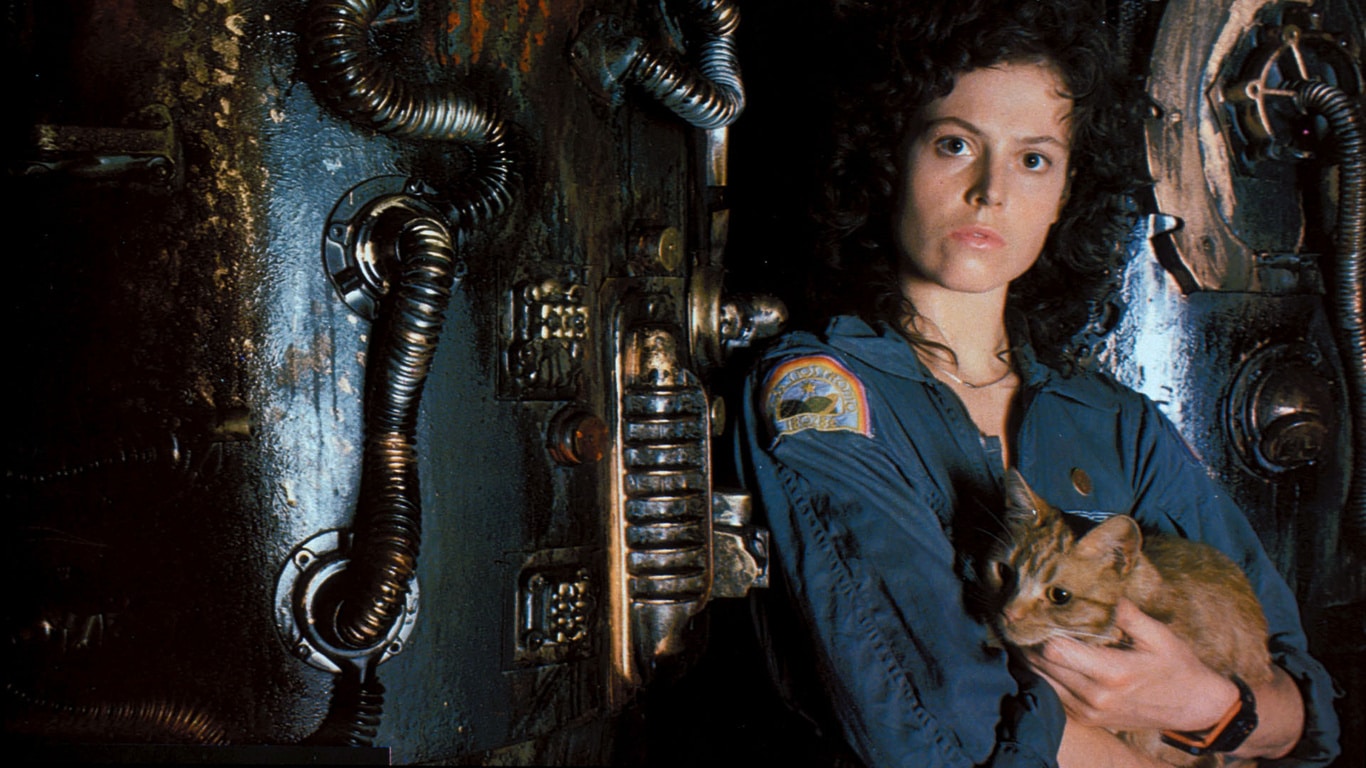

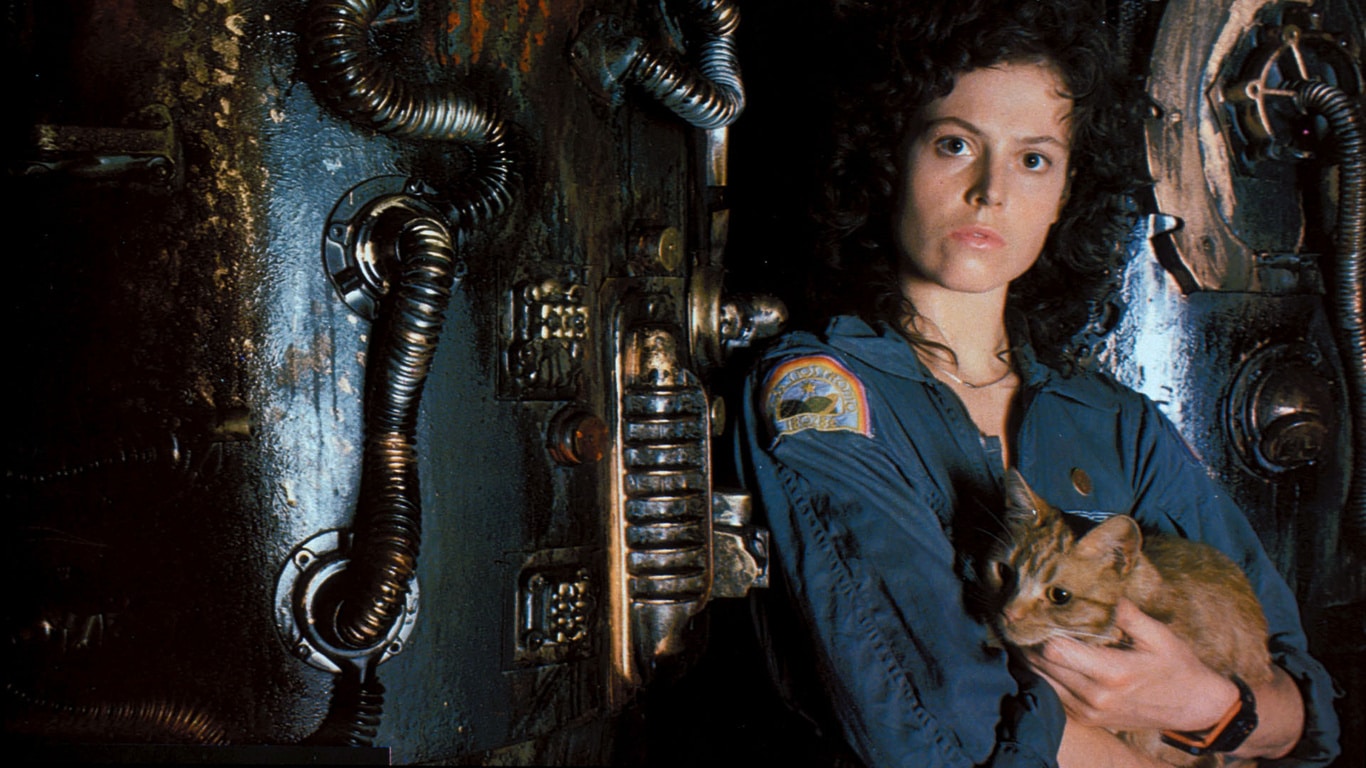

But then we met Jonesy, the unofficial eigth crew member of Alien’s Nostromo, and slowly but surely, the tide began to turn. Of course, we still got the random cat scares (Friday the 13th Part 2‘s is a particularly goofy one), but our feline furballs started appearing as actual pets more often, a perk that their canine counterparts had always enjoyed.

However, even with Jonesy (who briefly reappeared in Aliens, for he was so loved), cats started primarily being used as a shorthand to understand the threat of the movie; killing the cat (instead of a dog, because NOOOO) to give a hint at the dangers to come, or provide a catalyst to set the plot in motion.

Pet Sematary was the most famous example of this; it was a “Pet“ cemetery after all, so naturally, poor Church had to die for Louis Creed to learn about the place. Jud Crandall certainly wouldn’t have told him about it if little Gage had gotten run down first.

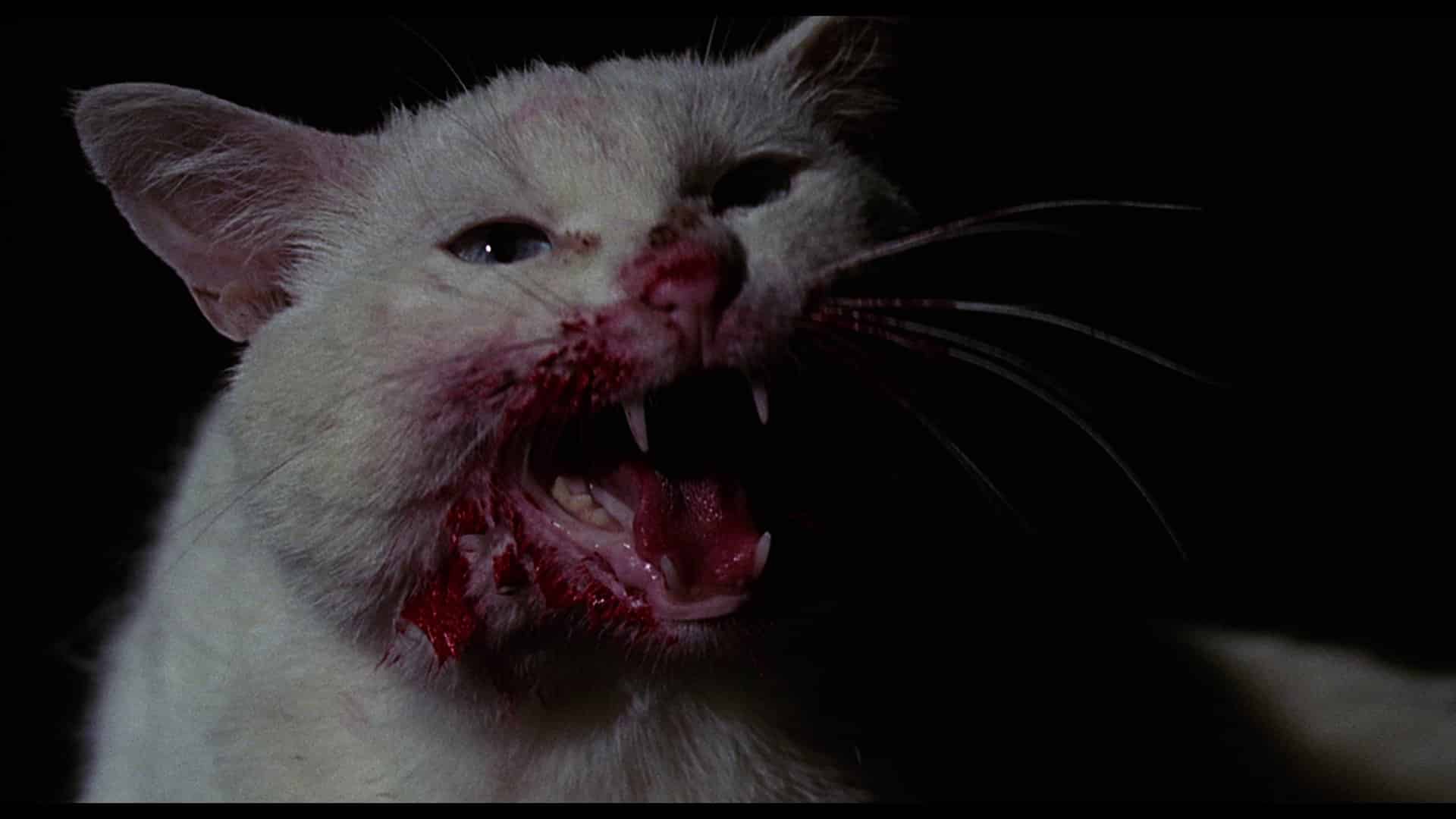

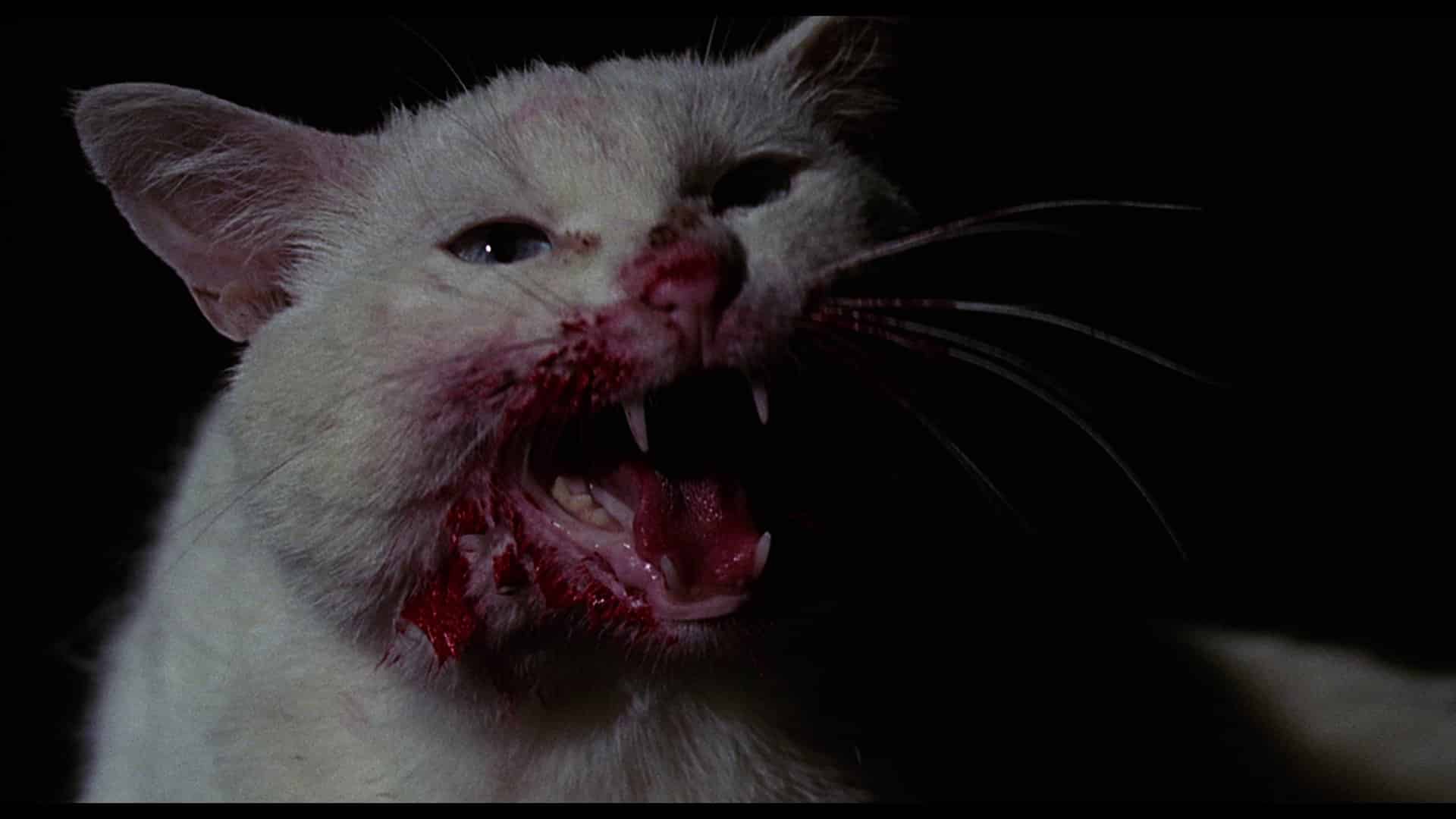

Another example is Of Unknown Origin, which is a humorous movie but might have gone into ridiculous territory if not for seeing how mangled an unlucky cat was after encountering the film’s villain: a normal (if slightly larger) New York City rat feasting its way through a yuppie’s gorgeous Brownstone. Once you see what it did to that poor cat, you will be just as fearful of it as Peter Weller. And who could forget Rufus in Re-Animator, whose death proved that Dr. West’s serum worked? (Cat dead, details later.)

But that sort of thing got reduced as well, and eventually, cats were not only allowed to survive the movie’s events more frequently but even became a way to remind us that some folks were human after all. A particularly good example was in 1995’s Species, when Michael Madsen’s ruthless mercenary character was introduced making sure his cat was cared for before heading out to take down Sil, so we knew he had a soft side.

We even had a few protective cats to even out the years of them being antagonistic, with 1985’s Cat’s Eye and 2008’s Let The Right One In allowing us a rare “Good kitty!“ response to some dastardly on-screen act. We still had evil cats, of course (Tales from the Darkside: The Movie, anyone?), but heroic ones were at least evening them out. It’s all about equality.

1992’s Sleepwalkers is sort of the alpha and omega of cat-based horror (at least tied with the 1977 anthology The Uncanny), as it offers pretty much everything discussed here. There’s an opening scene with a bunch of dead cats to tell us that the film’s villains are true monsters (and said scene has a surviving cat jump out and scare Mark Hamill). There’s a bunch of cats just sitting around doing very little. Our villains, the shapeshifting title characters, repeatedly fret about their presence and give the impression the cats are doing more than they actually are.

And then there’s Clovis, the film’s true hero, who saves heroine Mädchen Amick several times and leads the charge at the end when she and several other good kitties run and jump on the monstrous version of Alice Krige’s character.

And by now, they’re like dogs in that they don’t even have to really do all that much for us to root more for the cats than the humans. Just last year, audiences lost their minds in Eli Roth’s Thanksgiving when the killer, fresh off beheading a guy, noticed the man had a cat.

The killer looks at the little fluffball (who happened to be Dewey, the main cat from the Pet Sematary remake), and you tense up: is he going to kill the cat too? But then there’s a jump cut to a few moments later, where the killer (still masked) gives his new pal a little scratch as it devours the fresh food he clearly just laid out for it. And the audience cheers, seemingly forgiving the murderer for the human life he took moments earlier.

We’ve also seen a huge reduction in how often they are used as jump scares. I noted the one in Friday the 13th Part 2 earlier, and there’s a similar sequence in Argento’s Inferno that are both clearly being achieved the same way: someone just off camera tossing the cat (several of them in Inferno’s case) in front of the lens.

While cats are designed to be able to land on their feet and brush off such actions, it’s still a pretty mean thing to do. The American Humane Society has since stepped up its presence on productions (the “No Animals Were Harmed“ logo appears on pretty much every movie with an animal nowadays; this was not the case back then). It’s obvious that getting a cat to do one of these actions requires a little bit of manhandling that few would be comfortable with now. These scenes will not be missed.

This leads us to Frodo the cat in A Quiet Place: Day One, whose wellbeing seems more important to audiences than his human co-stars. Since he was prominently featured in the film’s marketing, more than one person noted on social media that they wouldn’t even be able to see it until they knew that the cat survived (spoiler for those who don’t know yet: Frodo lives!), but I didn’t see similar sentiments for Lupita Nyong’o or Joseph Quinn.

The movie’s franchise-high take for its opening weekend can be rightfully attributed to Frodo, I think, and it’s equally safe to assume that if he got munched on by one of the creatures, it wouldn’t have gotten the same B+ Cinemascore the first film enjoyed.

This sentiment has been offered for dogs forever (there’s even a website called Does The Dog Die?, though it’s expanded to other triggers over the years). But cats seemed to be fair game. Even as recently as 2009’s Drag Me To Hell, the cat’s death was played as a laugh, though such things are no longer in vogue.

When filmmakers decide the cat has to go, it’s usually depicted in a way that sells how horrific it is (2022’s Smile comes to mind), not for a laugh or even as a fake scare before the real threat appears moments later. Cats are just as great as dogs, dammit, and I, for one, am glad to see they’re now being treated with the same kind of love from both filmmakers and audiences alike.

For more, read what Frodo’s A Quiet Place: Day One co-stars had to say and deep dive into black cats in horror. And if you want to wrap your furry friend in style, maybe pick up one of our Fango bandanas.